Intensive Care Units are a canary in a coal mine

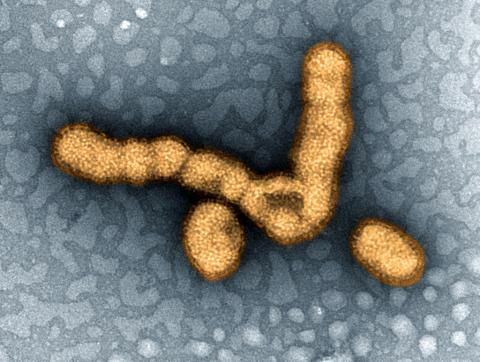

During the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic, the issue of how many deaths were associated to the emerging virus was one of the main causes of misunderstanding between authorities and the general public, which ended in a worrying lack of trust. The pandemic, initially presented as a potential serious threat, in the end was no more severe than a common seasonal flu. Unfortunately, even nowadays, it is difficult to ascertain if and how much H1N1 pandemic was different from any other seasonal flu, based on official data. An important source of problem is that, in the case of pandemic, health authorities declared only certified deaths, in which virological test had been made, while the mortality rate of seasonal flu is usually estimated as “excess mortality”, a rate of much bigger magnitude: the two, of course, could not be compared.

Anyway, even considering such a difference, it is true that the pandemic did not prove to be that lethal as feared in the beginning. Surely, its real threat did not lie in the number of victims, but rather in their characteristics: instead of hitting mainly old, ill or immunocompromised people, as any seasonal flu does, pandemic A(H1N1) killed young adults too, especially obese people, pregnant women, but also adolescents and children. A different set of targets that increased the emotional and socioeconomical burden of the disease. In most countries, such evaluations can be done only retrospectively, since official data about the causes of deaths and the demographic characteristics of the victims are available only after months or even years, hindering the possibility of a targeted, prompt and adequate response. In these situations, intensive care units (ICU) can be a canary in a coal mine, signalling any abnormal cluster of severe cases in specific groups. A real-time recording system of patients admitted in these wards, active and shared in a regional, national or transnational area, can somehow “filter” the huge amount of hospitalized patients in a given period. Therefore, it can draw attention to more severe cases, monitor their frequency and alert health authorities, in order to implement an appropriate response.

This is what happened early in 2013, when a possible new H1N1 epidemic was notified by an intensive care unit (ICU) to GiViTI, the Italian ICU network. This prompted the re-activation of the real-time monitoring system developed during the 2009-2010 pandemic. Based on data from 216 ICUs, GiViTI was able to detect and monitor an outbreak of severe H1N1 infection, and to compare the situation with previous years. GiViTI is an Italian ICU network, including more than 250 units, one of the largest all over the world, which collects data on about 90,000 patients/year. It also coordinates similar networks in other European and non-European countries (Slovenia, Hungary, Poland, Greece, Cyprus and Israel). Such a cooperation can be an invaluable tool to promptly detect an emerging serious infectious threat, as timely and correct assessment of the severity of an epidemic can be obtained by investigating ICU admissions, especially when historical comparisons can be made.

Guido Bertolini and Martin Langer, on behalf of GiViTI network, Italy