Vaccines: a case history of false balance on TV

Until the end, it seemed it could sort out to be a happy-ending story, a demonstration of how new social networks, renown for spreading misinformation, can also correct it, when used properly. But the unfortunately predictable finale showed the opposite: counteracting false ideas about vaccines is not that easy. It will take time, a big deal of patience, communication skills and a good, coordinated strategy as well.

Protagonist of this story is Roberto Burioni, an Italian virologist, professor at the Vita-Salute University San Raffaele in Milan. In the last months, the researcher became very popular at a national level for his Facebook posts about vaccines. With evidence-based, plain and simple arguments, he answers all the doubts families can raise about the issue. For his fame, he was therefore invited to a TV talk shows on the national state channel RAI 2, called Virus (not a scientific program, despite its name), led by a journalist named Nicola Porro.

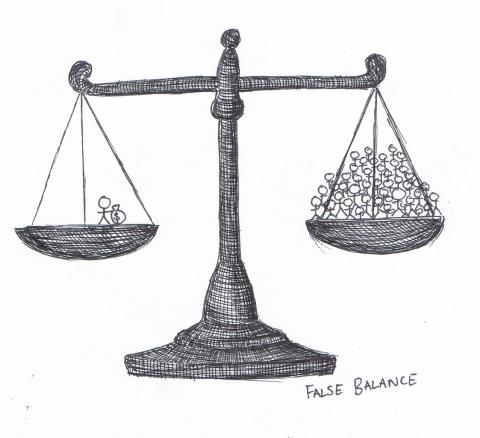

“I thought I would have had a chance to address a larger audience with good information about vaccines,” he says. On the contrary, he was given only few minutes through a link to Milan to rebut the hoaxes preached in the main TV studio by two questionable experts. One was Red Ronnie, a grown up DJ, who repeated the false and fraudulent connection between vaccines and autism, in addition to many other false circulating ideas. The other, even quirkier, was Eleonora Brigliadori, a former Italian actress, now dedicated to alternative medicines. She advocates against cancer therapies and supports fancy theories, such as the idea that drinking urine is healthy and that the growing number of babies born with microcephaly in South America is not due to zika virus, but to reincarnation of Spanish conquerors in them. At the end of the program, the public could not have got the right side of the story, and the only expert there, Roberto Burioni, defending vaccines, seemed to represent a minority, maybe moved by conflicts of interest with the pharma industry.

“I could not accept this,” declares Burioni, who denounced Red Ronnie for insinuating this. The day after he wrote an effective new post on his Facebook page, giving his version of the facts. This had a huge success. While the TV show had been viewed by something more than 1.200.000 people, Burioni’s post was shared by 46.000 persons and read by more than 5 million in one day. In the wake of tens of protesting voices coming from experts, science journalists, scientific societies and common citizens, rising up on Facebook and Twitter and addressing the Minister of Health, the Italian TV Surveillance Authorities intervened. It was stated that the program would not be allowed to continue next season, after the summer break. The idea that anyone could have his/her voice on any subject, even if when thousands of lives are at stakes, seemed to have been overcome. There are issues that are not a matter of free thought, on which some opinions have the same weight than others, and this is simply because they are not just ideas, but facts. The safety of vaccine is a fact, as well as their importance for preventing dangerous diseases.

Don’t count your chickens before they’ve hatched, anyway. When you win, it can be risky to aim at out-matching. This happened when Burioni was invited again to participate to the program the following week. “I thought that it was a remedial action and that the journalist had understood his mistake,” he says. But that was not the case. The expert was faced again by a lawyer who has made a business out of compensation lawsuits, parents convinced that their children were hurt by vaccines and an old philosopher, taken as an example of how also educated academics can be sceptical towards vaccines, who claimed for the idea that anyone is entitled to speak on the issue.

What is the moral of the story, then? Looking at the bright side, something is certainly moving. A growing number of people, whichever their jobs and competences, are now aware of the importance of vaccines and, more generally, of the risk of false balance in media. They are ready to raise their voices, especially when a bad communication can turn out to create risks for public health. However, it’s a long way before we can get a honest and responsible information by the media, where the same non-specialist journalists are allowed to deal with health and science as they do with politics. Maybe both print and radio-TV journalists all over the world should follow the same courses recommended by BBC in 2014, which invited its staff to “stop giving undue attention to marginal opinions”. If cranks can give a touch of colour in a sport programme, the same cannot be said when talking about science and health. This misinformation can put lives at risk. On these topics, everyone is requested a strong sense of responsibility.

Roberta Villa

On behalf of ASSET project